I had never read any of George Saunder’s work until recently, and The Semplica Girl Diaries was certainly a banger of an introduction. The weird diary-entry style of writing, the dumb insights of the narrator, and the intrigue of the SGs (Semplica Girls) kept me engaged throughout. By the end, I went, “What the heck did I just read”? I was scratching my head, in a good way, and I’m still thinking about it weeks later. One of the geniuses of this work is how it can juxtapose an outlandish idea while making it somehow normal, making the reader empathetic to heinous acts because they are done by someone we can identify with. This story raised questions that I’m still grappling with. Can a loving father, acting in the best interests of his children, fail to notice cruel acts happening right in front of him? The Semplica Girl Diaries propose that it can. The SG Diaries demonstrated that good, well-intentioned individuals can commit atrocities due to the narrowness of their perceptions, shaped by society’s acceptance and their own immediate but valid concerns. This was done subtly and effectively through an empathetic narrator, combined with a horrific possible future scenario.

The father and narrator of the story, for the most part, is an everyday man with problems that normally occupy a family man living in the suburbs of America. The family isn’t poor but isn’t well off either. They are a lower-middle-class family that struggles with paying off credit card bills and drives an old car that might be on its last leg. All these traits serve not only to draw sympathy from the reader but also to present the many conflicts that arise in the story. The narrator wants to be rich and provide everything for his family. He is a good husband and a good father. In a journal entry, he writes: “Just reread last entry and should clarify. Am not tired of work. I do not hate the rich. I aspire to be rich myself. And when we finally do get our own bridge, treehouse, SGs, etc. at least will know we really earned them.” (Saunders 119).

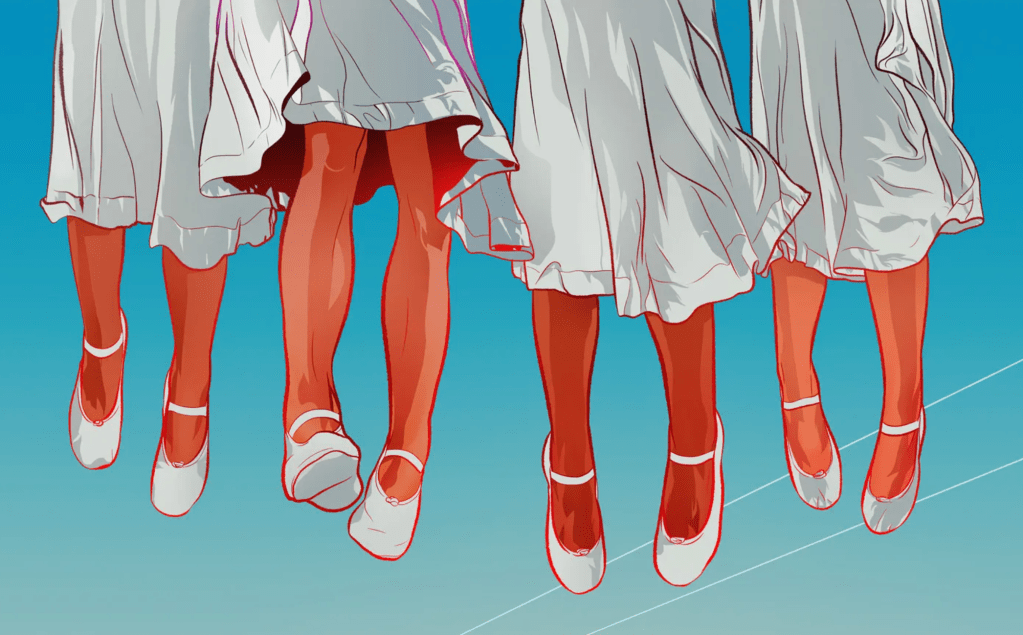

Despite being a good person, our protagonist lives in a world with a pretty cruel custom. At first, I thought the SGs were robots or perhaps some android slash artificial beings. The prose’s narration and the characters’ behavior make it seem like such a casual thing. What’s the big deal? Everyone is doing it! “Took Eva for drive. Drove through Eastridge, Lemon Hills. Pointed out houses w/SGs. Had Eva keep count. In end, of approx 50 houses, 39 had. (Saunders 141). The huge contrast between the warm portion of the story and the cruelty of the SGs made it even more disturbing. I wondered while reading, who would even think of writing a story like this? What would inspire such a plot line? Hunting down past interviews, I found a reference to the source of inspiration. In an interview for the New Yorker, Saunders was asked the very same question. He answered:

Well, it’s embarrassing. Somewhere around 1998, I had this incredibly vivid dream in which I went (in my underwear) to a (non-existent) window in the bedroom of our house in Syracuse and looked down into our backyard. Balmy summer night, beautiful full moon, etc., etc. … Then the yard came into focus, and what was out there was … as I describe in the story. And the weird(er) part was that, even having seen that, the “I” in the dream continued to be happy: “Jeez, just look at that, it’s so beautiful, and I was able to do that—man, I have really arrived.” (Treisman, This Week in Fiction, 2012).

And yet, from that tiny, weird dream, the story took more than a decade to write. In another interview, Saunders was teased, “You started in 1998 and finished in September of 2012, 14 years later”, to which he jokingly replied, “Yes, and thanks for bringing up that painful subject” (Ward and Saunders, slate.com, 2013). This obscene speculative element wasn’t the story’s main point because it would’ve been completed much sooner if it had been. Indeed, if this were the only element of the story, it wouldn’t have impacted me as much. Saunders himself reinforces this theory, he said:

The minute I woke up, I knew that the women in the yard were symbols for, you know, “the oppressed,”…that the story might turn out to be (merely) about that. In which case, who needs it, you know? If the only thing the story did was say, “Hey, it’s really wrong to hang up living women in your backyards, you capitalist-pig oppressors,” that wasn’t going to be enough. We kind of know that already. It had to be about that plus something else.” (Treisman, This Week in Fiction, 2012).

Regardless, the story’s theme of the exploitation of female migrant workers from impoverished countries is fairly obvious. Saunders effectively used this issue to highlight that anyone, no matter how decent, can inadvertently contribute to a major social injustice. The reader may ask if this is still a relevant topic. For those in more affluent countries, this problem may not be at the forefront of our daily thoughts. But this tragic practice is very much still going on today. According to the “Migration Data Portal” (www.migrationdataportal.org), a website dedicated to migration statistics, in mid-year 2020, there were about 135 million female migrants actively employed globally (Migration Data Portal). But are they treated well? A study from the Bangladesh Institute for Labor Studies among returned migrant women shows, “Up to half of them [the migrant female workers] were victims of violence or rape during their stay abroad. 52 percent were forced to work without pay. 61 percent did not get enough to eat and drink, and one in three was deprived of passports and other papers by the employer” (Ahamad and Rasmussen). It seems such cruelty still exists in the real world today.

Saunders must have real-life experience to use this subject in a short story. In a 2012 interview, he mentioned seeing the lives of migrant workers firsthand: “In 2003, I got sent to Dubai for a writing assignment, and it was like being surrounded by real-life SGs. The whole city was built and run by people who were contracted to be away from home for years at a time, were very low-paid, and were housed in horrific conditions, or, at least, the most poorly paid laborers were.” But he added: “And yet, there was another side to it, namely that a lot of the workers were wildly happy to be there, because, even given the hardships, they (and their families, to whom they were often sending their entire salaries) were far better off than they had been back home.” (Treisman, This Week in Fiction, 2012). This raises the question, is it okay to condone cruel practices and even use them if the victims themselves seem to be happy or volunteered for it? I’ve asked this question myself, replacing the extreme examples of the SGs with examples from our world, where we buy and consume products from harshly treated laborers and hire help from impoverished countries because they are cheaper. For example, I own an iPhone and a few other Apple products. I also recently learned about the conditions of the workers who made these products from factories in China:

Foxconn’s brutal work schedules, suicide nets outside buildings to catch falling bodies, corralling and abuse of interns, desolate atmosphere and indifferent safety practices are all part of a system that builds fortunes at extreme human cost. A commercial model in which a brand takes 50 per cent of the cost as profit is unusual, and so the wages and working conditions demanded by Foxconn are a direct consequence of Apple’s approach (Cormack).

But because these workers are essentially not forced into these inhumane jobs, and society has taken globalization for granted, we turn a blind eye to this unfair disparity, similar to the father in the story. He wrote in his diary after noticing the trauma the SGs were causing his daughter, Eva: “Note to self: talk to her, explain it does not hurt, they are not sad, but actually happy, given what their prior conditions were like; they chose, are glad, etc.” (Saunders 119). This is what the story brought my attention to. We make justification for our behaviors as much as the protagonist did. We are okay with contributing to systems of abuse even though we are decent human beings living decent lives. How much of this is okay? The far-fetched scenario of this story isn’t so crazy after all.

Eventually, the daughter sets the SGs free, which is a felony in their world. This turn of events puts our protagonist in a tough predicament, but it also causes him to start thinking about the actual predicament of the SGs. He started to wonder:

No money, no papers. Who will remove microline? Who will give her job? When will she ever see home + family again? Why would she ruin it all, leave our yard? Could have nice long run w/us. What in the world was she seeking? What could she want so much, that would make her pull such desparate stunt?” (Saunders 166).

This leaves the story on a hopeful note. Perhaps there is redemption for our protagonist after all. But before these conflicts were resolved, the story abruptly ended, leaving me scratching my head. The Semplica Girl Diaries subtly evokes complex emotions and questions by juxtaposing outrageous cruelty with a human voice and identifiable characters. It is simultaneously funny, disturbing, touching, and horrendous. Although I am curious about the fate of these characters, I realize that might not be the point. I am reminded of what my English professor recently said, “Fiction isn’t necessarily a puzzle in which we have to solve everything. It’s often about the reaction it evokes among us”. This story pretty much did that, evoking a strong reaction, and for me, that’s a story worth reading.

References

Ahamad, Rashad, and Henrik Lomholt Rasmussen. “Effektivt Våben Mod Udskamning af Migrantkvinder.” (Translation: Effective Weapon Against the Shaming of Migrant Women). Danish Trade Union Development Agency)

Ulandssekretariatet, 13 Oct. 2021,

https://www.ulandssekretariatet.dk/artikler/effektivt-vaaben-mod-udskamning-af-migrantkvinder/

Cormack, Mike. Dying for an iPhone: investigating Apple, Foxconn and the brutal exploitation of Chinese workers. April 2020.

https://www.scmp.com/magazines/post-magazine/books/article/3082307/dying-iphone-investigating-apple-foxconn-and-brutal

Migration Data Portal. “Gender and Migration.” Migration Data Portal, International Organization for Migration, 2024,

https://www.migrationdataportal.org/themes/gender-and-migration

Saunders, George. “The Semplica Girl Diaries”. Tenth of December. Random House. 2013. New York.

Treisman, Deborah. “This Week in Fiction: George Saunders.” The New Yorker, October 4, 2012. https://www.newyorker.com/books/page-turner/this-week-in-fiction-george-saunders-2.

Treisman, Deborah. On “Tenth of December”: An Interview with George Saunders. The New Yorker, Jan 24, 2013. https://www.newyorker.com/books/page-turner/on-tenth-of-december-an-interview-with-george-saunders

Ward, Andy and George Saunders. The Slate Book Review author-editor interview. slate.com January 07, 2013

https://slate.com/culture/2013/01/tenth-of-december-author-george-saunders-in-conversation-with-his-random-house-editor-andy-ward.html

Leave a comment